Baldrige and C3: Diagnosis and Treatment Plan

Chapter 22 from Mastering Excellence: A Leader’s Guide to Aligning Strategy, Culture, Customer Experience & Measures of Success

Written by Brian Lassiter

Setting the Context: The History of Baldrige-Based Performance Excellence

In the wake of the last Great Recession (though we didn’t call it that back then) in the 1980s, America was in trouble. The country suffered a two-phase recession from 1980 to 1982 that left unemployment high and interest rates even higher. (Recall credit cards and mortgages well beyond 20 percent!) A fragile banking and savings and loan system caused the economic challenges, but one of the other root causes that’s not as frequently discussed is quite simple and fundamental: America had stopped focusing on the customer.

To give you just a little context, post–World War II, America was productive and economically vibrant. To rebuild infrastructure left dormant during the war—and to begin to create more modern luxuries like televisions, automobiles, and appliances—manufacturing produced at nearly full capacity. As a result, except for a few minor blips, the United States enjoyed one of its longest periods of economic expansion from 1950 to 1975. So much so, I would argue, that there was little incentive for US manufacturers to pay much attention to product quality or the needs of the customer. Businesses would just keep making stuff, and people would keep buying the stuff.

What is Baldrige?

Today the Baldrige Framework has become the de facto definition of performance excellence not only in the United States, but throughout the world. More than eighty countries have similar frameworks and award programs based on Baldrige. Also, today thousands of organizations across the country are using the Baldrige Framework. There are many practitioners in all sectors: manufacturing, service businesses, health care systems and hospitals, educational institutions (both K–12 and higher education), nonprofits of all types, and governmental agencies. Why? Because the principles of quality not only work in making widgets but have also been proven to work in every type of organization. And the principles of quality have proven scalable, from the large, complex multinational businesses to the small mom-and-pop shops and rural school districts and everything in between.

The Baldrige Framework has become a management system to help leaders better understand how their enterprise is working, of what processes might be considered strengths that need to be maintained or leveraged, and what might be considered opportunities for improvement. In other words, Baldrige has become a diagnostic system to help leaders identify strengths and improvement opportunities, so they focus their precious resources on improving the right things that create the most value for customers, workers, shareholders, and other stakeholders. In many ways, Baldrige can be viewed as the annual physical for your organization. It provides an opportunity to check its pulse and to systematically improve those things that matter the most to organizational health.

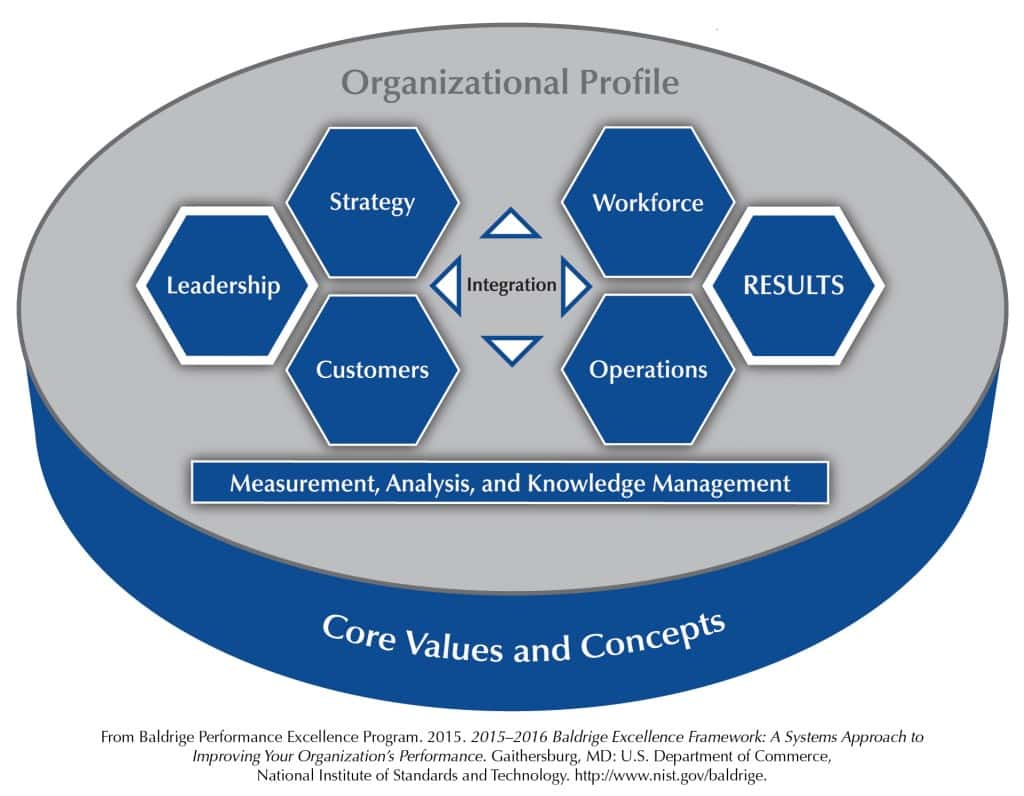

The Baldrige Framework has seven categories, six of which represent a collection of processes and the seventh that represents outcomes that an organization is trying to achieve. Under categories 1 through 6 sit a collection of about 270 high-level, open-ended, non-prescriptive questions that each imply a process.

Some of the questions include the following:

- How do senior leaders communicate with and engage the entire workforce and key customers?

- How does your strategy development process stimulate and incorporate innovation?

- How do you build and manage customer relationships?

- How do you determine key drivers of workforce engagement?

- How does your day-to-day operation of work processes ensure they meet key process requirements?

For each question, organizations should have a systematic approach (a well-ordered, repeatable, data-based process) that’s widely deployed (across organizational locations, units/departments, shifts, and so forth), systematically evaluated and improved (the closed-loop refinement cycle that ensures processes are kept current with organizational needs), and are aligned (and, in some cases, integrated) with other organizational processes.

The Baldrige questions (the Criteria for Performance Excellence) change every couple years by studying and understanding what high-performing organizations are doing to achieve excellence, vetting those practices, and then including them in future versions of the criteria. In this way, the Baldrige Framework has become what’s now called the “leading edge of validated management practice.” It is truly a set of best practices against which any organization can gauge its performance, identify gaps, optimize resources, and rapidly improve and sustain outcomes. This makes the framework powerful. It’s not theory or someone’s good ideas, but rather it’s an evidence-based system that includes processes and management principles that truly drive outcomes.

But the often untold story behind the story was this: a gentleman by the name of W. Edwards Deming, often credited for creating the modern quality movement, was imploring US manufacturers to use his principles to improve processes and product quality and focus on the worker and the customer. He could see the waste in most American enterprises, but he couldn’t get their attention to address it. When the perception was “it ain’t broke,” there was no incentive to fix it.

So he went to Japan in the early 1950s, espousing the principles of quality, and the rest, as they say, is history. Japanese products, processes, and companies quietly but significantly improved in the 1950s and 1960s, creating what would be a competitive force to the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. Companies like Toyota, Datsun (now Nissan), Sony, and others flourished and started taking market share from US companies who had become complacent and possibly a bit arrogant.

When those forces collided—a major US economic correction in the late 1970s and early 1980s coupled with the rise of postwar Japan—public- and private- sector US leaders realized that businesses needed to operate in a different way to stay competitive in an emerging world market. The now seminal NBC television episode “If Japan Can, Why Can’t We?”—which aired on the NBC White Paper series in the early 1980s—is now credited for creating the US quality movement. The show outlined many of the principles that Japanese manufacturers used to optimize resources, engage workers, focus on customers, and drive quality, principles that Deming had taught Japan some thirty years earlier. America was playing catch-up and needed to galvanize US manufacturers to improve performance or risk becoming the number two economy to Japan.

In 1987, the US Congress approved the creation of the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award, named after the Secretary of Commerce Mac Baldrige, who had suffered an untimely death by falling off a horse in a rodeo accident. The program was to be managed by the Department of Commerce, specifically the National Bureau of Standards (now called the National Institute of Standards and Technology), where it still resides today. The legislation created an award program to recognize those organizations that have demonstrated superior quality and other performance results (such as financial, customer-related, workforce-related, and leadership). But more importantly, the Baldrige Program attempts to shine a light on best practices that advance the principles of excellence and improve organizational results.

The Alignment with C3

But here’s the deal: Baldrige is intentionally non-prescriptive. It doesn’t tell leaders how to manage their enterprises. That’s probably appropriate, as no two organizations are alike. They operate in different environments (even in the same industry). They are pursuing multiple strategies. They have several core competencies, and they are addressing different strategic challenges. As an example of the non-prescriptive nature of the framework, Baldrige does not declare that you must use Lean or Six Sigma to achieve superior operational results. You may, of course, but you don’t have to. There are other appropriate tools that help organizations achieve superior operational outcomes.

So this is where C3 comes in. At its core, the purpose of C3 is to change the culture of an organization so that its strategy, the design of its products and services, and its daily operations are all aligned with customer priorities. It sounds simple. And I think it sounds appropriate. Most organizations would say that they want their enterprise to be aligned with, perhaps driven by, customer priorities. But saying and doing are two very different things. And being truly customer-focused is challenging because so many organizations are self-centered. Rob Lawton, the architect behind C3, would claim that most organizations are producer-centered, not customer-centered. And his C3 method is the prescriptive answer to the critical questions Baldrige asks about being customer-focused.

The similarities of intent and philosophy between Baldrige and C3 are many:

- Both have as a central goal total customer satisfaction. In fact, Baldrige encourages organizations to have processes to measure customer satisfaction, dissatisfaction, and engagement, the latter meaning that customers are willing to make an investment in or commitment to the organization’s brand and product offerings.

- Both believe quality can and should be designed into service, not only addressed after the fact as an outcome of the service.

- Both require organizations to determine customer groups and segments because both realize that no two customers are created equal. Customers have different needs, priorities, roles, and behaviors. Segmenting them helps organizations sort through those differences, aligning products and services to address varying needs. The alternative is whitewashing customers all the same, which rarely produces satisfying customer outcomes.

- Both state that customer requirements should drive product, service, and process requirements. And both declare that organizations should have measures to ensure that products and processes are delivering against those requirements.

- Both state that organizations should make not only continuous improvements (to its products, services, and processes) but also develop breakthrough improvements that create new value for customers. Baldrige defines this as innovation, and it’s a theme throughout the framework. C3 refers to this as pursuit of excellence, going beyond what is required.

- Both focus on outcomes. C3 states that many organizations focus too much on features and functions of a product, not the outcomes that the product is trying to create for the customer. I tend to agree. And if you focus on desired outcomes first, then you can work backward into the features and functions that support a better customer experience.

- Both offer a systems perspective of the organization, meaning both believe that all components of the organization should be understood, managed, and aligned as a unified whole to fully achieve the organization’s mission, to maximize value for customers, and to achieve and sustain performance excellence. Most improvement approaches only consider part of the system, which almost by definition will suboptimize the system. To its credit, C3 focuses on the interconnected nature between customer and producer, helping organizations, much like Baldrige does, to improve alignment across various processes.

C3 has a few other prescriptive suggestions that Baldrige doesn’t address, which makes it useful. Some include:

- A fundamental principle of C3 is that there is a difference between being producer-focused (the organization putting its own needs first) and being customer-focused. To fully achieve a customer-centered culture, organizations should view their enterprise through the lens of their customers. Their strategy should be framed through the perspective of the customer. Their products and services should obviously be designed to satisfy customer needs. Their processes should be designed to achieve positive customer outcomes. Their workers should be trained and equipped to fully satisfy customer needs.

- C3 suggests that organizations should define services in terms of products. Why? Because defining service is ambiguous, which makes it extremely difficult for organizations to know when they’ve fully satisfied customer requirements. Instead, if services are defined as products, the organization can think in more concrete terms and can better define and deliver against customer needs. The trick, C3 says, is to call services by a noun. Examples include a plan, a speech, a report, or a meeting. Once a service is defined as a product, more concrete outcomes can be identified, measured, and achieved.

- When segmenting customers, organizations should think in terms of end user, broker, and fixer and should always first try to satisfy end user customers. End users are individuals (or organizations) who use the product to achieve a desired outcome. While it is often assumed they are the ones who write the check, so to speak, the reality is that another kind of customer does that— the broker. The adage “follow the money” reveals that brokers may have very different priorities than end users, but their grip on the money creates distraction. Brokers transfer the product to someone else who will use it, either as an agent of the end user or an agent of the producer. And fixers transform, repair, or adjust the product at any point in its life cycle for the benefit of end users. These distinctions are helpful in considering how organizations should segment customers and also prioritizing which customers are more important than others. C3 makes clear the frequent lack of alignment between importance and power when it comes to customers.

- C3 suggests that organizations should strive to significantly reduce time in their processes. In fact, it suggests that the redesign of processes be aimed for zero time or at least to strive for cutting out 80 percent of the time of any given process. Time as a requirement is fairly universal across products and customer segments. While traditional quality systems strive to reduce process variability, cost, and defects (which are important), time is a customer requirement often overlooked by organizational producers.

Summary

The need to improve your organization’s performance has perhaps never been greater. Today, customers expect more, competent workers are growing scarce, competition is intensifying, technology and information are accelerating, and business models are changing at increasing speeds. But with the complexity of today’s organizations, making random improvements is no longer enough. Organizations need a system, and they need a way to better understand how processes are currently working and a systematic pathway to make change to create new value for customers. The Baldrige Framework provides an excellent lens through which to diagnose and set priorities for improvement, and C3 provides a useful approach to significantly transform an organization’s culture to focus on the customer. Making that change may be more important today than ever.